Dreamthorp; A Book of Essays Written in the Country by Alexander Smith

I shall not pretend that this paper was prepared without some care, and as I read over my rough notes it suddenly occurred to me to re-read a volume of essays by Alexander Smith, who is remembered, if he is remembered, by one small volume of essays called Dreamthorp, published before I was born. I have a first edition of this book, and taking it from its place on my shelves, I opened it and to my amazement read in a paper entitled "On the Writing of Essays" much that I have said about Montaigne; this is not surprising, for everything that can be said about Montaigne has been said–– as about Shakespeare: the only thing that remains is to say it in a new way. But I also came upon this: "Jacques in 'As You Like It' has the making of a charming essayist and the essayist is a kind of poet in prose." I was not consciously pilfering from Alexander Smith when I wrote, a few days before, identically the same thing. I don't think I have dipped into Dreamthorp for several years; I read As You Like It only a few weeks ago. and I was struck at the time that the romantic Jacques, who is usually lying under a greenwood tree when he delivers his famous soliloquy, would have been a fine essayist if he had not been a finer thing––a fine poet. Reading further on, I came upon this: "It is not the essayist's duty to inform ... incidentally he may do something in that way just as the poet may, but it is not his duty." I was just going to labor this point, and I shall not be turned aside from the fact that a better man than I has done it before me.

Morley gave five presentations as the Rosenbach Fellow in Bibliography in 1931. But rather than call them lectures, he called them conversations. His third conversation, entitled "Three Kinds of Collectors," contained his comments on Dreamthorp. And in this conversation he mentioned being introduced to Dreamthorp via Thomas B. Mosher's catalogues:

... it was in one of Mosher's catalogues that I first heard of Dreamthorp, a book which is not widely known, and yet I feel that a casual soliloquy like this would justify itself if it did nothing more than introduce a dozen new zealots to a book like Dreamthorp. Some of you may be interested in writing essays. Alexander Smith's sketch in that book, called "On the Writing of Essays," is the wisest and most communicative thing ever said on that subject. His essay on Christmas, Christmas of the year 1862, is one of the loveliest things ever written about Christmas, one of the most poignant, and this is the time of year to re-read it. It was written not long before his death; perhaps already, in his fine phrase, he had "the candle of death in his hand," that casts a softened light on human scenes....

Both A. Edward Newton and Christopher Morley praised Alexander Smith's essay entitled "On the Writing of Essays." I extracted a portion of it to use as the opener for my essay, A Virtual Tour of My Collection of Essays, that I posted on My Sentimental Library blog in May, 2014:

When Alexander Smith wanders about Dreamthorp, or when he talks about his library shelves, he turns up surprising nourishment. He is worth following closely. His essays are of an older fashion but no one has ever spoken more pleasantly of the essayist's purpose and privilege, or the perplexities of the life of letters.... A sad book, I found myself saying: it has the delicious gift of melancholy. In all the years that I have loved this book I have never cared much to identify Dreamthorp itself (very likely it is largely imaginary) nor to rummage out the details of Smith's life.... All the comments on him that I have ever seen say that he "died of overwork." What, then: this delicious picture of indolence and ease, loafing about the village, gardening, reading, is it all fiction? The pose as an old gentleman is also fiction, for we know that he was only 34 when this book was published––and died at 36. I can't help getting a grin when he speaks––in the essay on Death and the Fear of Dying––of the man of thirty as such an aged veteran.... Let none be deceived by his pretended posture of seniority: this is a young man's book; young even in its instinctive return to sombre themes. It is odd that teachers have not made more use of it; it has extraordinary things to say about literature, things almost worthy of Lamb; and he introduces his ironies so quietly that you might think them not ironical but just Scotch. "To be publicly put to death must be a serious matter." And finally, in Dreamthorp the enthusiast has one of the most selfish refinements of booklovers' delight: it is a book that only the very few have heard of....

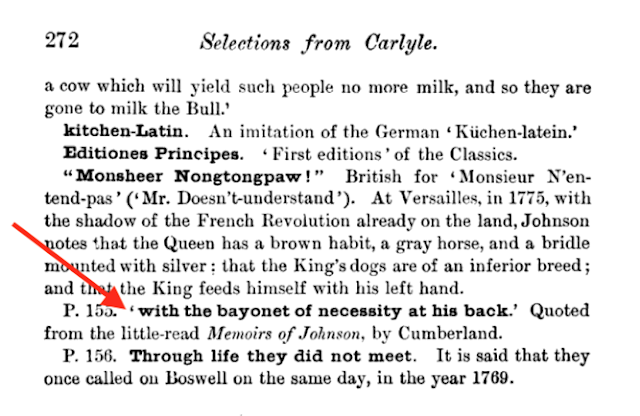

Morley's comments on Smith's use of ironies and being publicly put to death refers to Smith's essay on capital punishment entitled, "A Lark's Flight." Just as two men are about to be executed at the scaffold, a lark suddenly flies up in the air and begins to sing.

Morley wasn't the only one who mentioned Alexander Smith writing about his library shelves in one of his essays. I replicated Smith's special shelf in my own library and wrote about it on my blog, The Displaced Book Collector:

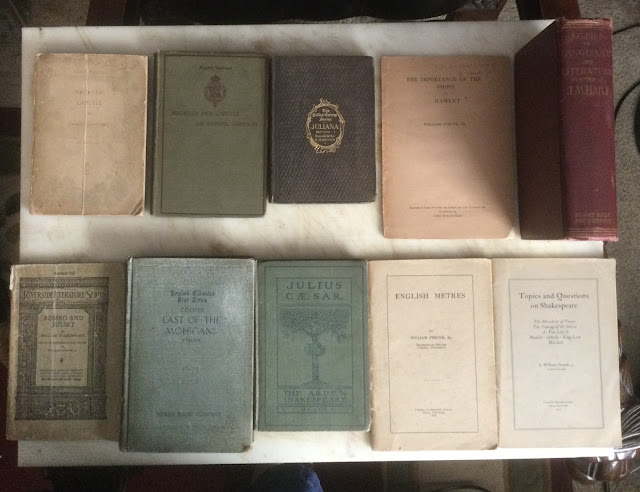

I wrote this blog post in June 2007 while watching my grandchildren in Hawaii while their father was serving a tour in Iraq with the U. S. Air Force. I couldn't include a photo of the shelf in the post because the books were still in Florida. So here's a photo of the entire shelf. It extends from wall to wall above my library closet. I intended to align the shelf with book chotskys, but decided to place some of the books from my Poetry Collection there instead. Located in the far right corner of the shelf are copies of the Poetry books and other books mentioned in Smith's shelf.

Not shown in the photo below is a copy of the Doubleday, Doran publication of Dreamthorp that I acquired to replace a copy of Dreamthorp that I had given to a friend. And shown in the photo, but not mentioned in my 2007 post, are three books that I added to the shelf: Tales By Nathaniel Hawthorne, and two Torch Press books, both by William Harvey Miner: Charles Churchill, Vagabond Poet and Savage–The Rake; Chatterton–The Precocious Youth; Two Eighteenth Century Character Sketches.

Now back to Morley! Further on in his Introduction to Dreamthorp, Christopher Morley himself places Alexander Smith on a special kind of shelf:

He belongs on a shelf with those very special favorites of the tenderest passion––with Lamb, and Hunt, and Hazlitt and Ryecroft; with Sir Roger and Walden and Santayana. Or perhaps with that supremely Scottish classic, now too much forgotten, Galt's Annals of the Parish. If you were to put him not too far away from his idol Montaigne, then (in the words of the younger Scot) "There he lies where he longed to be." Some day I must look up his biography. I can't quite believe that a man so wise would allow himself to be killed "of overwork." Let us remember that!

As an aside, there were numerous reports that Alexander Smith died of overwork. However, his death certificate lists diphtheria/typhoid fever as the cause of death. Smith contracted diphtheria in November of 1866, which was then compounded by typhoid fever. He died on January 5, 1867. Here is a photo of his grave in Warriston Cemetery in Scotland.

It was the Bibelot Vol XIX issued in 1913 issue that Morley later said was how he discovered Dreamthorp. Thomas Bird Mosher had reprinted an essay about Alexander Smith by James Ashcroft Noble that was published in the Yellow Book in 1895. The essay was entitled "Mr. Stevenson's Forerunner." Morley was on a Stevenson kick at the time and said that he hastened to read the piece. Morley agreed that Noble's article title was justified because he could see interesting parallels in Stevenson's Lay Morals and Apology for Idlers to Smith's essay, Vagabonds.

Thomas Bird Mosher himself had a few words to say about Dreamthorp in his Foreword to the 1913 Edition of the Bibelot:

For Dreamthorp, –– the book with the beautiful title –– has lived in the world fifty years and from now on, if we mistake not the growing indifference to merely smart-set writing of all sorts –– is called to a renewed and longer lease of life. All things considered it belongs in that little collection of precious age-defying books which never disappoint their reader and never grow old. It has the natural magic of simple, exquisite style: it is a book we love well enough to mark our favorite passages in, and not feel ashamed of doing so....

Mosher also mentioned in his Foreword that he previously had a few words to say about Smith in the Foreword to the 1909 edition of the Bibelot. That issue contained an essay by James Smetham, which was first published in the London Quarterly Review in October 1868 as a review of Smith's posthumous work, Last Leaves; Sketches and Criticisms. As another aside here, I was surprised that Smetham made no mention whatsoever of Dreamthorp in his essay – not even mentioning the title! Yet he discussed all of Smith's other works including The Life Drama and City Poems. But now, back to what Mosher had to say about Smith and Dreamthorp:

Smith, who died in 1867, "the prey of overwork," came suddenly into his own with the issue of The Life Drama (1853). He somewhat expanded his poetical outlook in City Poems (1857), and in his one play, Edwin of Deira (1861). But, whatever may have been the estimate of the pasionate few, we are come to a period of the dispassionate many, and he is only known now as the author of Dreamthorp: A Book of Essays Written in the Country (1863), which is still an ideal book for fireside companionship. "Poet and Essayist" was the epitaph chosen for him, and as an essayist he will remain as he desired: "To be occasionally quoted is the only fame I care for."

In my June 2007 post, A Shelf In My Bookcase, I mentioned that one of the books on my shelf was Luther Brewer's Torch Press edition of Smith's essay, A Shelf In My Bookcase. Here are some of things Luther Brewer said about Dreamthorp and its author in the Foreward to his edition of the book:

Dreamthorp, a book of essays written in the country, his first venture in prose, appeared in June, 1863, and went through six editions in less than two months. These essays are delightful reading and have been favorites. They have the reminiscent flavor of the writings of our own Ik Marvel. They are full of a quiet charm; they evince sympathy with nature. "Never," said a writer in the London Literary Times, "since the days of Charles Lamb, who is an especial favorite, by the way, of Mr. Smith, has such charming prose been presented to the world. This, indeed, is high praise, but it is warranted fully.

In the belief that the bookish flavor and the breath of outdoor life to be gotten from the reading of the essay which follows will delight, it is republished in this form. It is a pleasure to remember the work of an author who can write such a clever thing.

Mr. Smith died as the result of overwork, January 5, 1867.

I included an extract from A Shelf in My Bookcase in my Aug 2013 post, Elegant Extracts About Books, Booklovers, and Libraries:

And finally, a word of caution! If you agree with A. Edward Newton, Christopher Morley, Thomas Bird Mosher, Luther Brewer, and yours truly, that a copy of Dreamthorp belongs in your bookcase, make sure that you acquire an edition of Dreamthorp that includes all twelve essays. The Peter Pauper Press edition contains only eight of the essays. Not included are A Shelf in My Bookcase, A Lark's Flight, Christmas, and William Dunbar.