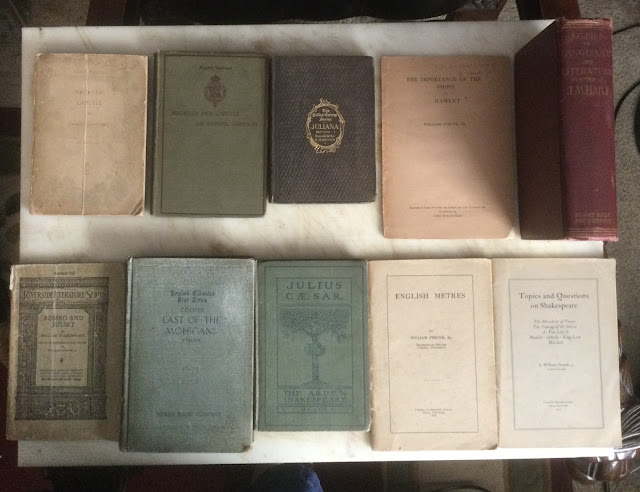

The Elements of Style, William Strunk Jr's little book, is the little book that E. B. White made famous. But that's not the only book of his. Here are some of his other books.

Not listed but headed my way from Saucony Book Shop is a copy of All For Love and the Spanish Fryar by John Dryden edited by William Strunk Jr. Boston: D. C. Heath, 1911.

I was even more delighted after reading Strunk's comments in the very first paragraph of his Introduction concerning the sources of Johnson and Boswell that are mentioned in the essays of Macaulay and Carlyle.

The first great authorities for the lives of the two are Boswell's Life of Johnson and Tour to the Hebrides. Besides the great literary excellence of these works, their great veracity and accuracy are unquestioned. The other sources for Johnson's biography, mentioned in the two essays, add little to what Boswell tells, and are of interest chiefly to annotators of the Life. Mrs. Thrale gives some anecdotes not found elsewhere, it is true, but her book has no serious value; it is merely amusing. Hawkins is proverbially dull, and has an air of giving information at second hand. Tyers gives merely a rambling collection of gossip, told in commonplace fashion. Murphy, a professional man of letters and a personal friend, wrote a life of Johnson as one of his literary commissions, just as he has previously written a life of Fielding; satisfactory performances in their day, but now obsolete.

The great Johnsonian collector, R. B. Adam, thought enough of the book to acquire a copy for his Johnsonian Collection.

|

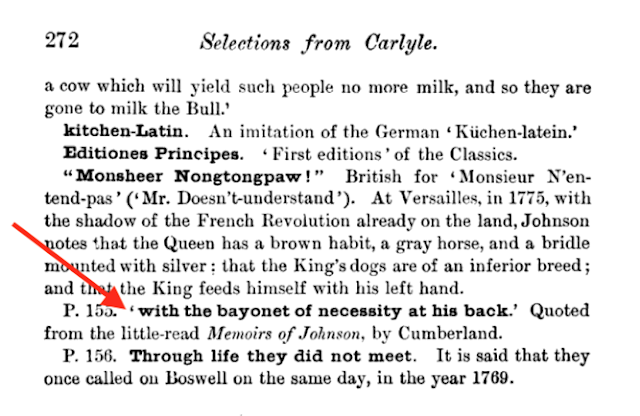

Another literary critic, Henry Walcott Boynton, thought so highly of Strunk's book that he provided the same notes in his 1896 book, Selections From Carlyle, that Strunk used in his book, often with the same exact words. Strunk called Boynton out on this plagiarism in a March 1897 letter to the editors of Modern Language Notes (Jstor). In the letter, Strunk mentioned that the Johnsonian, George Birkbeck Hill, informed him of a mistake in the title of a book by Richard Cumberland cited in one of Strunk's notes. Strunk corrected the error in the second edition of Strunk's book. And he chided Boynton for not consulting the second edition before copying the note.

Strunk's Notes to the 1895 Edition

Boynton's Notes to His Book

Strunk was one of the editors of a festschrift of essays collected and published in honor of James Morgan Hart 70th birthday in 1910. Hart was a fellow professor at Cornell who was retiring. Hart was a professor at the University of Cincinnati when Strunk was attending college there in the late 1880s. He finished hs academic career as a professor at Cornell.

Strunk contributed his essay, "The Importance of the Ghost in Hamlet," for the book. He gave a copy of the offprint to Frederick Tupper, an English Language professor at the University of Vermont. This offprint, inscribed by Strunk himself, is now in my library.

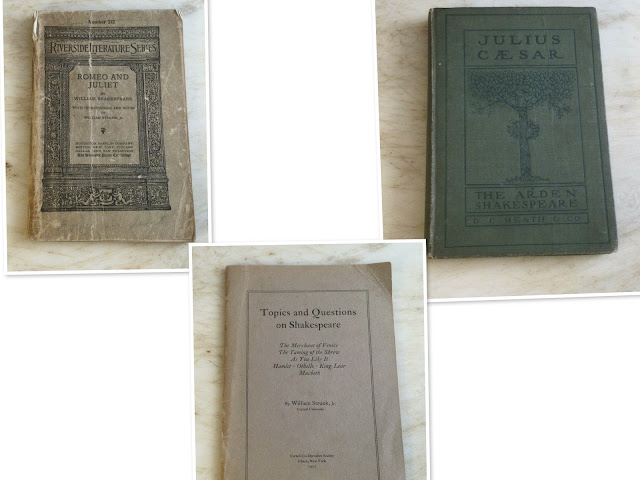

Strunk edited two of Shakespeare's works, the Riverside Press edition of Romeo and Juliet in 1911, and D. C. Heath's Arden Shakespeare Series of Julius Cæsar in 1915. In 1927, the Cornell Co-Operative Society published his pamphlet Topics and Questions on Shakespeare. The Cornell Co-Operative Society previously published his pamphlet, English Metres, in 1922.

Strunk's biggest claim to fame during his lifetime was being chosen in 1935 as the literary adviser for the MGM movie production of Romeo and Juliet. Irving Thalberg had been trying to get his studio to do a film production of Romeo and Juliet for years, and finally, in 1935, the studio gave him the go ahead to do the production. Thalberg wanted the most eminent Shakespeare authority in America to be the literary adviser for the film. And the Folger Library recommended William Strunk Jr. Thalberg wanted the film version of Romeo and Juliet to be as close to Shakespeare's version of the play as possible. He told Strunk, "Your job is to protect Shakespeare from us."

I have two books about the movie: a souvenir program and the motion picture edition published by Random House in 1936. Strunk wrote the Introduction for the Random House edition, explaining why a mivie production was the best avenue to present SStrunk's play. The photo of Stunk displayed above is illustrated on page 256 of the book.

For more than the past ten years, I have been corresponding with Jim Myers, whose father, Henry Alonzo Myers, was a professor of English at Cornell, and one of William Strunk's long-time friends. Jim mentions his father's friendship with Strunk, in an article in the June 1977 issue of The Cornell Alumni News that is titled "A University of the Mind." His father, while still a graduate student, was the secretary of the Cornell Department of English. The job consisted of two duties: listening to William Strunk, and writing letters to job applicants informing them that no jobs were available.

By far the best Strunkian anecdote that Jim Myers ever told me was when Strunk was turning his English class over to Myers before departing for Hollywood. Strunk's desk was covered with books. And as Strunk was hurrying out the door, Myers asked, "What should I do with the books?" Strunk yelled back, "Keep them!"

Henry Alonzo Myers kept Strunk's books. And now his son Jim Myers has them. He also has letters that Strunk wrote to his father on Hollywood Hotel Stationary. In the letters, Strunk writes about the actors and actresses he met on the movie set.

I asked to buy some of Strunk's books from Jim Myers, and even asked for copies of some of the letters. But he has other plans for what he will do with them.